Across Scotland, a preventable crisis is quietly unfolding. Childhood vaccination rates are falling just as global outbreaks of once controlled diseases gain momentum, leaving our youngest children increasingly vulnerable. This threat has been amplified by recent political upheavals in the USA and UK where policy changes have slashed aid for international immunisation programmes, creating conditions where preventable diseases can flourish and spread across borders. Growing vaccine skepticism fuelled by rhetoric from the USA and compounded by post-pandemic vaccination fatigue is undermining public confidence in one of medicine’s greatest achievements. The evidence for childhood immunisation remains unequivocal: these programmes have saved millions of lives and freed generations from the fear of devastating diseases. Yet today in Scotland, we are witnessing a troubling reversal. Vaccination uptake is plummeting in rural communities and areas of high deprivation, creating a stark health inequality that threatens to divide our nation’s children into the protected and the vulnerable. Unless we move swiftly to restore confidence in vaccination and ensure equitable access across all communities, we risk allowing preventable suffering to take hold among Scotland’s children. The time to act is now, before this widening gap in protection becomes a public health catastrophe we could have prevented.

Significant changes to the delivery of vaccination programmes occurred in Scotland following the introduction of the 2018 Scottish GP contract. Responsibility for much of the national childhood and seasonal vaccination programme was transferred from Primary Care (GP surgeries) to the Health Board–led Vaccination Transformation Programme (VTP), delivered primarily through large, centralised vaccination hubs. This transfer occurred between 2021 and 2023. This policy change blocked most GP practices in Scotland from ordering, storing, and administering vaccines, even when opportunities arose, a phenomenon I term “empty fridge syndrome”. GP’s are no longer able to directly intervene when a vaccine opportunity appears; we now refer a patient to the vaccine service, which may be located some distance from the practice. At the outset of this policy change, several primary care team members involved in community vaccine delivery warned that implementing it in certain locations could cause delays, reduce vaccine uptake, and result in harm.

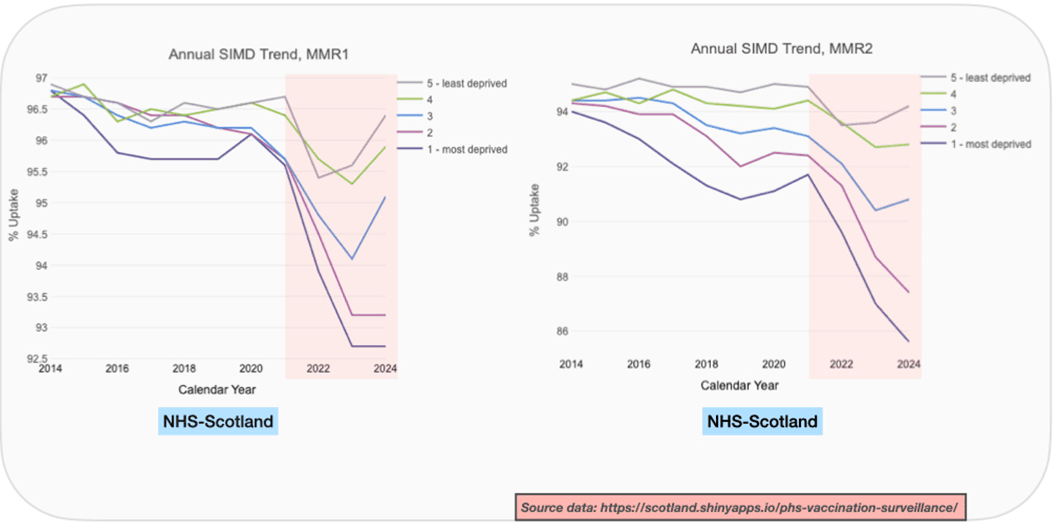

For this discussion, I use measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMR) uptake as the example, but a similar pattern is seen across most pre‑school vaccinations. Since the introduction of VTP, the uptake gap – the difference in percentage of children taking the vaccine – between the least and most deprived children has widened. Source data from Public Health Scotland, published on 30th September 2025, demonstrated minor recovery in the least deprived groups, but not in the population groups living in areas of deprivation (SIMD 1and 2); in these groups, uptake is falling and this gap is widening. The VTP model of delivery may be influencing this health inequality for families in more deprived areas, with the effect potentially greatest in remote towns, places without proximity to a major vaccine delivery hub.

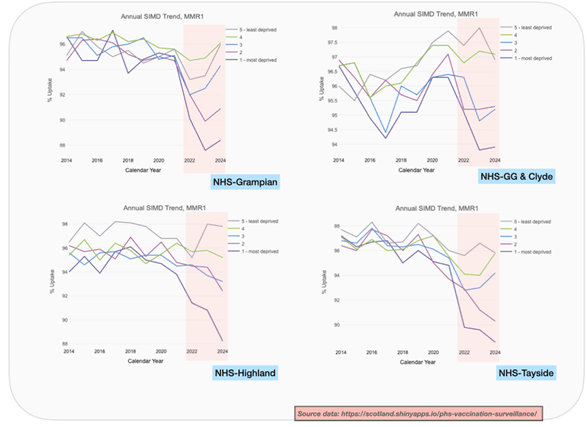

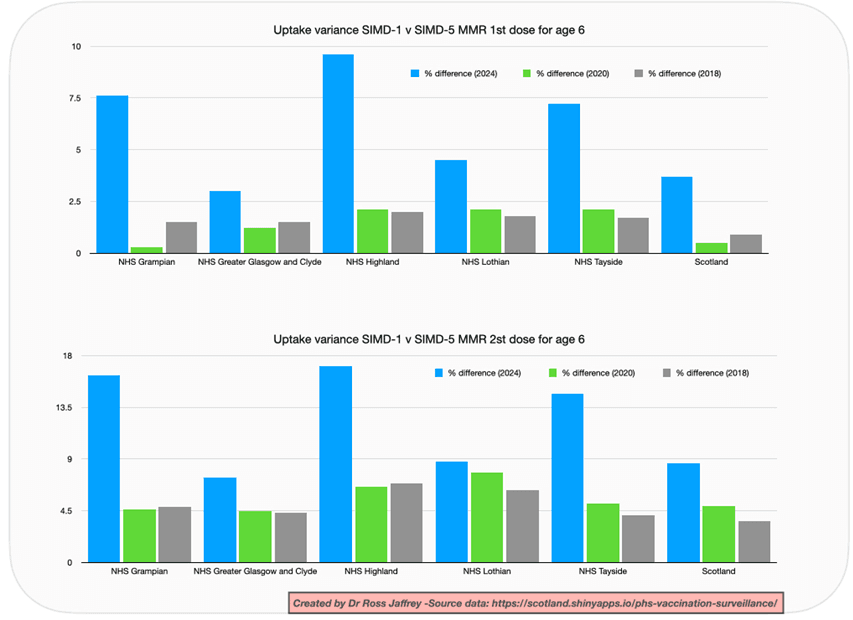

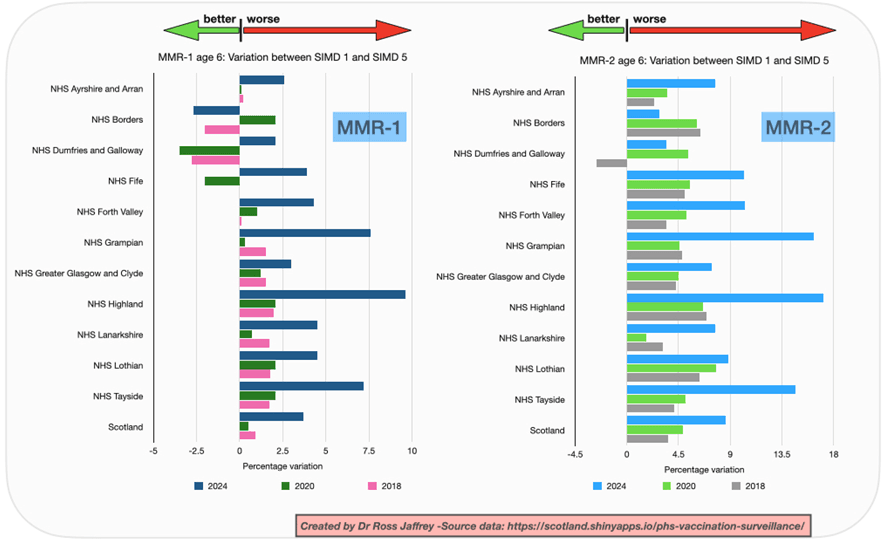

Measles remains a rare disease in our country. Scotland reported 24 cases in 2024; a single case was reported in 2023. The potential for re-emergence of this virus within the community is a real and growing threat; 28 measles cases have been reported so far this year. The impact of measles should not be underestimated. England has reported 772 cases and 1 death in 2025. In 2024, the European region reported 127,350 cases of measles, with children under five accounting for 40% of all cases. The United States and Canada have also faced widespread outbreaks that strain local health services, sparking public fear and much finger pointing over accountability. While measles is often regarded as an unpleasant but self-limiting illness, it can be severe, particularly in young children, leading to long-term complications. There is no specific antiviral treatment for measles; management is generally supportive once the infection is contracted. Prevention remains the most effective strategy to mitigate harms caused by this disease. The MMR vaccine has been a key part of the UK immunisation programme since its introduction in 1988. It is safe and highly effective, providing over 95% protection against the disease with two doses. Achieving high levels of vaccination coverage is essential to protect communities through herd immunity, WHO recommend at least 95% uptake. Maintaining this level of coverage has proven to be a global challenge due to several factors: issues with access, vaccine availability, vaccine misinformation, and vaccine hesitancy. Scotland’s rates should not be affected by the first two, but these may have influenced uptake in rural regions and within areas of deprivation following the change in delivery to VTP. The first childhood dose MMR uptake in 2024 for NHS-Scotland by 24 months was 92.8%, previously when GP practices delivered this part of the programme uptake remained above 94% (2013-2022). This slight decline in uptake nationally fails to fully unmask a significant and evolving problem in our most deprived areas, the largest drop-off in vaccine uptake is occurring in these population groups (SIMD 1 and 2). Prior to 2020, the largest gap between least and most deprived children for MMR-1 in children aged 6 was less than 1%, this is now 3.7%, equivalent to approximately 1300 children missing vaccination per year. Clearly, the pandemic had some impact from 2021 but trends are now recovering in the least deprived groups, but not in the most deprived groups. The steepest decline is evidenced in NHS-Highland, the board area I work in. MMR-1 uptake variance between the least deprived (97.8%) and most deprived (88.2%) is almost 10%, a 3-fold increase since the change in delivery system. For MMR-2, this gap becomes 17.1% (only 75.6% of children have both vaccines in SIMD 1). These trends are not unique to NHS-Highland. The MMR booster uptake in children aged 6 for NHS-Tayside demonstrate a similar trend with a 14.5% uptake gap between least and most deprived, NHS-Grampian evidences a 16.4% gap; historically, these health inequality gaps were never as stark. Primary schools in areas of deprivation are likely to be significantly more vulnerable to measles outbreaks because of this variance. Why is this happening and being permitted to continue?

The VTP was welcomed for easing pressure on GP appointments. In 2018, the BMA, together with the Scottish Government, negotiated the removal of vaccination from the national GP contract. However, many Highland GP, and others across Scotland, wanted to keep vaccinations within general practice. They feared the change would weaken the vital link between GP teams and the families they care for, and make vaccination services harder to access. For many young families, vaccination visits were their first contact with the GP practice. These appointments gave staff a chance to spot other health needs early and support overall wellbeing. Administrative teams took pride in encouraging attendance, and time was set aside to discuss parents’ concerns if hesitancy to attend occurred. Since the move to central vaccine hubs in larger towns, with fewer, smaller clinics in outlying areas, services feel less flexible and more impersonal. Travel can now be significant, adding costs for low‑income families and hitting rural communities hardest. Many community clinics are not open five days a week and do not stock the full range of vaccines that practices once carried. Some vaccines are available only on specific days, and siblings of different ages often cannot be seen together. The current VTP setup makes it difficult for GPs to view a child’s up‑to‑date vaccination record. A child’s full immunisation history may no longer be held in one place, and it can be hard to access quickly. This data‑sharing problem was known before the change and still hasn’t been resolved. For such a critical service, that should not have happened.

Allow family doctors do what they do best: protect patients and utilise our highly skilled local Primary Care teams to help address the widening health inequality being observed in childhood vaccine uptake. Scotland’s 5 year immunisation plan, published in November 2024, identified 4 key priorities: equitable access, make every contact count, strengthen capacity and capability, and to use a system wide approach. A main goal was to reduce inequalities. Unfortunately the data paints a different picture, without significant change to the current model many children in several regions will be let down despite a cohort of health professionals trying their best to prevent it. Family doctors have the expertise, trusted relationships, and systems to deliver it efficiently and equitably. Yet current policy prevents most GPs in Scotland from ordering, storing, and administering vaccines directly. Fridges in surgeries remain empty. This must change.

Vaccination remains available through the national VTP service. If your child is eligible and not yet vaccinated, please book with your local vaccination team now. Measles, and other vaccine-preventable illnesses, are real, immediate threats. We should not wait for a significant outbreak to act.

Dr Ross Jaffrey, GP based in Highland

REFERENCES

- https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/european-region-reports-highest-number-measles-cases-more-25-years-unicef-whoeurope (published 13th March 2025)

- Global immunisation funding shortfall/cuts https://www.gavi.org/news/media-room/world-leaders-recommit-immunisation-amid-global-funding-shortfall

- Public Health Scotland: Immunisation and vaccine-preventable diseases quarterly report

- April to June 2025 (Q2) https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/immunisation-and-vaccine-preventable-diseases-quarterly-report/immunisation-and-vaccine-preventable-diseases-quarterly-report-april-to-june-2025-q2/results-and-commentary/pertussis/

- GP contract Scotland 2018 https://www.gov.scot/publications/gms-contract-scotland/

- https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/childhood-immunisation-statistics-scotland/childhood-immunisation-statistics-scotland-quarter-and-year-ending-31-march-2025/

- https://publichealthscotland.scot/population-health/health-protection/infectious-diseases/measles/data-and-surveillance/disease-surveillance

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/measles-epidemiology-2023/confirmed-cases-of-measles-in-england-by-month-age-region-and-upper-tier-local-authority-2025

- EU statistics: https://measles-rubella-monthly.ecdc.europa.eu/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book#the-green-book

- Di Pietrantonj C et al. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD004407. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5

- https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/scotlands-5-year-vaccination-and-immunisation-framework-and-delivery-plan/

These graphs demonstrate the MMR trends for SIMD groups from 2014 to 2024 for the first dose uptake by age 6. WHO recommends uptake of 95% as the gold standard. NHS-Scotland last achieved this in 2021. The pink shaded area denotes the time period the VTP model was introduced in most Health Board areas within Scotland, 2022 onward. All Health Boards had use of the VTP by 2023. Below is the breakdown for SIMD groups by Health Board. I selected 4 Health Boards for comparison: NHS-Grampian, NHS-Greater Glasgow and Clyde, NHS-Highland and NHS Lothian. Falling trends in SIMD 1 and 2 groups is not solely an NHS-Highland phenomenon.

The tables above evidence the variation in uptake from most to least deprived. The percentage variance evidences a significant reduction in uptake between the most deprived and the least deprived childhood population groups in Scotland, SIMD 1 v SIMD 5. NHS-Highland performs poorly, as do NHS-Grampian and NHS-Tayside. All three share a larger geographic area, and likely have fewer transport links to main vaccine hubs. Inequality gaps are also observed in the larger board areas for NHS Lothian and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

These graphs demonstrate the variation of MMR-1 and MMR-2 uptake between mainland NHS-Scotland Health Boards in children aged 6. Any right shift equates to a poorer uptake in the most deprived population groups. Most Health Boards demonstrate a significant worsening of uptake in 2024 when comparing to years 2020 and 2018. Only one Health Board area – NHS-Borders has demonstrated a higher uptake in the SIMD-1 group compared to SIMD-5. This occurs in MMR-1. These gaps between socio-economic population groups may have significant impacts on future preventable disease outbreaks in schools.